How to turn a health app into a marketable digital health application (DiGA) - Part 2

Published on 1st December 2020

"App on prescription": Digital health applications on the fast lane into the standard care of statutory health insurance companies

In the second part of our four-part series of articles "How to turn a health app into a marketable digital health application (DiGA)", which deals with the opportunities and challenges for health apps in the German digital health market, Larissa Mößmer examines the essential requirements of a health app as a so-called Digital Health Application (“Digitale Gesundheitsanwendung” - DiGA) on the way to reimbursement by the statutory health insurance companies.

There is a gold-rush mood among the developers of health apps in Germany: The "app on prescription" is here! On December 19, 2019, the German Digital Healthcare Act (“Digitale-Versorgung-Gesetz” - DVG) came into force and paved the way for certain health apps to become part of the standard health insurance system, thus facilitating access to the public health system in Germany, one of the largest health markets in the world.

Whereas in the past the costs of such medical applications had to be largely borne by the users themselves, around 73 million people with statutory health insurance now have a right to be provided with DiGAs. These are medical apps that can be prescribed by doctors and psychotherapists in Germany at the cost of the statutory health insurance companies. This makes Germany the first country in the world to offer the "app on prescription" at the expense of the public health system and therefore a very interesting market for digital healthcare providers and investors.

Legal framework:

A triad of laws regulate the authorisation and reimbursement of digital health apps.

The new Section 33a and Section 139e of the Fifth Book of the German Social Security Code (“Fünftes Buch Sozialgesetzbuch” - SGB V), which were newly created in implementation of the DVG, for the first time, create a regulatory framework for the approval and reimbursement of these "apps on prescription".

For example, Section 33a (1) SGB V now contains the right of the insured patient to be provided with digital health apps if these:

- meet the requirements and the procedure for inclusion in the directory for digital health applications (DiGA directory), maintained by the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (“Bundesamt für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte” - BfArM) in accordance with Section 139e SGB V; and

- have been prescribed by a doctor or psychotherapist or approved by the statutory health insurance company.

These provisions of the SGB V are flanked by the so-called Digital Health Applications Ordinance (“Digitale-Gesundheitsanwendungen-Verordnung” - DiGAV), which came into force on 21 April 2020 and specifies the details of the requirements of DiGAs and the so-called fast-track procedure for inclusion in the DiGA directory and the eligibility of these DiGAs for reimbursement.

The triad of legal regulations is rounded off by the so-called DiGA Guideline („DiGA-Leitfaden“), an explanatory interpretation aid for the material criteria and procedural specifications of the DVG and the DiGAV for the fast-track procedure, also issued by the BfArM at the end of 2020. By issuing this guide BfArM set the final piece for the new legal framework and the kick-off for its implementation.

Legal requirements of a DiGA

At the beginning of the path of a health app into the standard care of the statutory health insurance companies, the first question that arises is which apps are DiGAs, i.e. digital health applications in the sense of the DVG, and which ones fall outside the scope of a possible reimbursement from the outset.

The legal definition contained in Section 33a (1) SGB V describes the legal requirements of a DiGA as follows

"[Digital health applications are medical devices] of low risk class whose principal function relies essentially on digital technologies and which are intended to assist in the detection, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of disease or the detection, treatment, alleviation or compensation of injury or disability in the insured or in the care provided by healthcare providers (digital health applications) “

According to the legislator's concept, the DiGA should thus serve as a "digital assistant" in the hands of the patient, which is why sole practice equipment apps are not covered by the term.

Medical device of low risk class (Class I or IIa)

The decisive criterion for a DiGA is initially its certification as a medical device of a low risk class I or IIa according to the EU Medical Device Regulation (MDR) or, until its validity begins on 26 May 2021, within the framework of the transitional provisions according to the Medical Device Directive 93/42/EEC (MDD).

In this respect, particular attention should be paid to the reference in Section 33a (2) SGB V regarding the application of the transitional provisions of the MDR. For example, according to Section 120 (3) and (4) MDR, medical devices that already bear a valid certificate according to the MDD and that continue to meet the requirements of the MDD from the date of the MDR's commencement of validity on 26 May 2021 can still be placed on the market on the basis of the old risk classification.

In part 1 of our four-part article series, you can read why this transitional provision is a real competitive advantage for "first movers" and why it is therefore worthwhile to certify a health app as a medical device before May 2021, as well as more information on its classification as a low-risk medical device.

Main function based on digital technologies

A further requirement is that the DiGA’s main function is essentially based on digital technologies; in other words, that its medical purpose is achieved precisely through the main digital function. Therefore, for example, a communication channel (via video, chat) between doctor and patient is not sufficient, but the "intelligent" algorithms of the software must themselves fulfil an immediate medical function. Thus, although in principle either a native app or a desktop or browser application could be classified as a DiGA, the application must not only be used to read out other devices and transmit data; the software must also analyse and process the data.

The difficulty of distinguishing between the existence of a refundable DiGA and a non-refundable combination product has been criticised in relation to this criterion. The DiGA Guideline of the BfArM contains more detailed explanations in this regard. According to these, in addition to software, devices, sensors or other hardware (e.g. wearables) are also to be classified as DiGA, as long as:

- the main function is predominantly digital,

- the hardware is necessary to achieve the purpose of DiGA and

- it is not an object of daily life that is to be privately financed, such as a smartphone for implementing the exercises instructed by the DiGA.

Exclusion of primary preventive and lifestyle apps

Due to the purpose of a DiGA regulated in Section 33a (1) SGB V to support the "detection, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of diseases" or the "detection, treatment, alleviation or compensation of injuries or disabilities", pure "lifestyle apps", which means apps that only serve to promote a healthy lifestyle in general (e.g. fitness trackers, calorie counters) as well as purely primary preventive apps are excluded from the reimbursable scope from the outset.

In contrast, apps that help to prevent the worsening of a disease state (secondary prevention) or to avoid secondary diseases and complications (tertiary prevention) are covered by the term "treatment" and therefore by the legal definition of a DiGA.

The path to reimbursement

The prerequisite for the reimbursement of a DiGA by the statutory health insurance companies is its successful completion of a quick examination procedure before the BfArM, the so-called fast-track procedure, and the subsequent listing of the app in the DiGA directory.

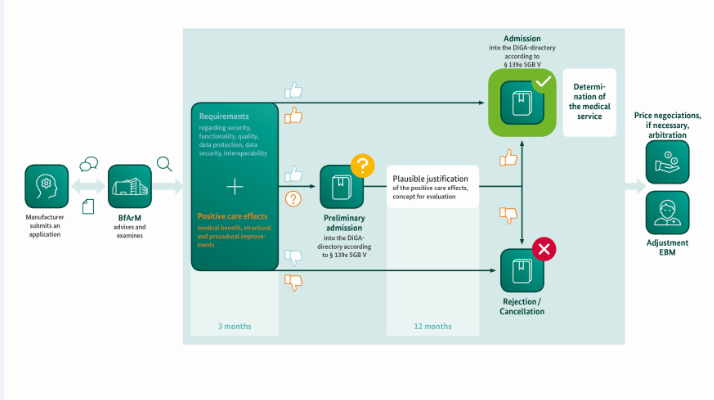

Overview of the fast-track procedure

The fast-track procedure is regulated in Sections 1 et seq. of the DiGAV and begins with an application for inclusion in the DiGA directory to be submitted to BfArM by the manufacturer or a third party duly authorised by the manufacturer. In the following three months the BfArM examines whether the app is a DiGA within the meaning of Section 33a SGB V according to the criteria described above and whether it fulfils the requirements for inclusion in the DiGA directory as regulated in Section 139e (2) SGB V and, finally, whether there are any reasons for exclusion.

The core of the procedure is the examination of the product requirements regarding safety, functionality, quality, data protection and data security (for more details, look out for part three of our four-part series of articles) as well as the examination of evidence to be provided by the manufacturer for the co-called positive care effects (“Positive Versorgungseffekte”) realisable with the DiGA.

After successful completion of the test procedure, the app will be included in the DiGA directory either permanently or, if a DiGA fulfils all other requirements but cannot yet provide proof of positive care effects, preliminary for 12 months (but for a maximum of 24 months). Within this trial phase, the manufacturer must then provide the required sufficient evidence of positive care effects.

The following diagram of the BfArM illustrates the essential steps of the fast-track procedure for the inclusion in the DiGA directory:

Source: BfArM, 2020, "The Fast-Track procedure for digital health applications (DiGA) according to § 139e SGB V. A guide for manufacturers, service providers and users".

Concept and proof of positive care effects

The "positive care effects" within the meaning of Section 8 DiGAV to be proven by the manufacturer are either a medical benefit or patient-relevant structural and procedural improvements in health care. According to this definition, “medical benefit” is the patient-relevant effect in terms of improvement of the state of health, shortening of the duration of illness, prolongation of survival or improvement of the quality of life. Patient-relevant “structural and procedural improvements” in care are aimed at supporting the health action of patients or integrating the processes between patients and healthcare providers.

Both terms thus refer directly to the patients themself. The effects of a DiGA on the workload of medical staff or economic key figures of healthcare are therefore not suitable as non-patient-relevant endpoints for the proof of positive care effects, but can play a role in the later negotiation on the remuneration of the DiGA with the Central Federal Association of the Statutory Health Insurance Funds.

The proof of positive health care effects must be based on a retrospective or prospective quantitative comparative study, which shows that the use of digital health care applications is better for patients than their non-use. The specific requirements for the concrete study design are described in Sections 10 et seq. DiGAV as well as in the DiGA guidelines of the BfArM, which provide more detailed information, and are illustrated with numerous examples.

Inclusion in the DiGA directory and reimbursement

If the DiGA fulfils all test requirements and if, at the time of application, proof of its positive effects on health care can already be sufficiently demonstrated by corresponding studies, the DiGA will be finally included in the DiGA directory.

If this proof of positive care effects is not successful, a provisional listing of the DiGA is possible upon application for a trial period of initially a maximum of 12 months, which can be extended once for a further 12 months. As a prerequisite for this, Section 139e (4) SGB V stipulates that the manufacturer must present a plausible justification of the DiGA's contribution to improving supply and a scientific evaluation concept prepared by a manufacturer-independent institution to prove positive care effects. During the trial phase, the manufacturer must then provide the required evidence for the existence of positive care effects on the basis of corresponding studies.

After inclusion in the DiGA directory, the DiGA is finally reimbursed provisionally for one year by the statutory health insurance companies at the actual manufacturer price. The price from the second year onwards is then negotiated between the manufacturer and the Central Federal Association of the Statutory Health Insurance Funds (we will look in more detail at the reimbursement for DiGAs in Part 4 of our four-part series).

Outlook

The long-term effects of the still very recent new legal regulations on the reimbursement of digital health apps on the German health market are difficult to assess at this point in time. Nevertheless, there is little doubt that the market will receive an enormous boost from the new fast-track procedure and the corresponding facilitation of market access and monetization of health apps.

The next few months will show whether the legal regime, intended as a fast-track procedure, is practicable enough to really pave a fast way for DiGAs to enter the system of standard care and thus reimbursement by the statutory health insurance companies.

As of end of November 2020, 40 applications have already been submitted to the BfArM for inclusion in the DiGA directory, five of which have been approved and none of which have been rejected, so far. The current list of already permanently or preliminary included DiGAs can be viewed publicly on the BfArM website.

Author: Larissa Moessmer (Associate at Osborne Clarke)