New draft code to tackle APP fraud, but questions remain unanswered

Published on 7th November 2018

This Insight follows on from our previous article which looks at the rising problem of customers being tricked into sending money to fraudsters – known as authorised push payment (APP) fraud.

The Authorised Push Payments Scams Steering Group (the Steering Group) was created by the Payment Systems Regulator earlier in 2018 and was given two main tasks:

- to design a reimbursement model that assumes that there is a requisite standard of care that both payment service providers (PSPs) and ‘customers’ (which is limited in scope under the proposals to consumers, microenterprises and small charities) must meet and to decide when a customer is entitled to reimbursement and when he/she/it is not; and

- where firms are required to reimburse customers, to design a funding model for that reimbursement.

The aim is to ensure that APP scam victims are compensated whilst also incentivising PSPs to invest in and maintain practices that help prevent and respond to APP scams.

On 1 October 2018, the Steering Group published a consultation paper and draft industry voluntary code (draft Code). The timetable that the Payment Systems Regulator set for producing the draft Code was, by its own admission, ‘ambitious’; and this probably explains why these papers do not contain proposals to address the two most difficult and fundamental issues:

- who should meet the cost of reimbursing victims where both the PSPs and the victim have taken the requisite level of care (a 'no blame' scenario); and

- whether victims should be reimbursed if neither they nor the relevant PSPs have met their levels of care.

Responses to the consultation paper are requested by 5pm on 15 November 2018. A final code is expected to be published by the Steering Group in early 2019.

What is the scope of the draft Code?

The draft Code:

- covers all PSPs;

- applies to APP scams only, meaning that that the payment involved must be authorised in accordance with the terms and conditions for the relevant payment account;

- applies to payments between GBP-denominated, UK-domiciled accounts that are made by consumers, microenterprises or small charities (referred to collectively as ‘customers’);

- is ‘payment channel neutral’ – meaning that it applies regardless of how a customer interacts with their PSP to authorise a payment, be it by telephone, online banking, or a mobile app; and

- applies only to PSPs involved in authorising and processing the transaction from the victim to the first generation account.

The Code will not be expected to apply to APP scams that took place before it is published in final form. From that date, FOS will be able to take the Code into account when determining the outcome of consumer complaints about APP scams.

How is the draft Code expected to work?

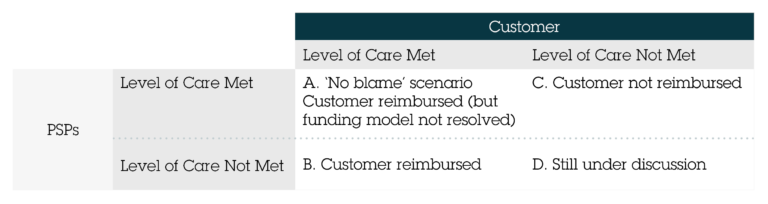

The Steering Group has created the table below which summarises its proposed reimbursement outcomes and shows which areas have not yet been resolved.

Which areas have been resolved?

The draft Code establishes that, if a customer has met the requisite level of care, PSPs will always have to reimburse the customer (scenarios A and B in the table), although how reimbursement is to be funded in cases where both the PSPs and the customer have taken the requisite level of care is unclear.

It has also been established that if a customer has not met the requisite level of care, then provided the PSPs have complied with the best practice standards set out in the draft Code, the customer's PSP will not have to reimburse the customer (scenario C in the table). What remains unresolved is who bears the loss when neither the PSPs nor the customer have taken the requisite level of care (scenario D in the table).

When is a customer deemed not to have taken the requisite level of care (Scenario C in the table)?

According to the draft Code, this will be where:

- the customer has ignored effective warnings given in compliance with the draft Code;

- the customer has not acted to prevent the fraud following a negative confirmation of payee result;

- the customer has not checked that the payee was the person they wanted to pay;

- the customer has recklessly shared their personal security credentials or allowed access to their online banking app or site;

- the customer has not acted openly and honestly with the PSP;

- the customer is a microenterprise or charity and has not followed its own internal procedures to prevent the fraud; or

- the customer has been grossly negligent (see What is 'gross negligence'? below).

PSPs should always take their own culpability into account as well as whether different customer behaviour would have had a ‘material effect’ on preventing the APP fraud. They should also consider whether the customer is particularly ‘vulnerable to APP fraud’ - if he or she is vulnerable, then the customer's PSP cannot refuse reimbursement in any scenario (see When is a customer 'particularly vulnerable' to APP fraud? below).

The decision not to reimburse a customer should be made by PSPs ‘without undue delay’, and in any event within 15 business days of the customer reporting the APP fraud (this can be extended to a period up to 35 days in exceptional cases and provided the customer is appropriately notified).

What is 'gross negligence'?

This is a good question.

The origins of the concept of 'gross negligence' for these purposes are not founded in common law principles of tort, rather they can be traced back to the first Payment Services Directive 2007 which introduced it as an undefined concept. In order to incentivise customers to notify PSPs of the theft or loss of their cards as quickly as possible, customers are liable only for a limited amount in the event of unauthorised use of the cards, unless they have acted fraudulently or 'with gross negligence'. In 2015, the second Payment Services Directive sought to put some colour around the concept, describing 'gross negligence' as 'more than mere negligence' and 'conduct exhibiting a significant degree of carelessness’, with one example cited being keeping a PIN with a card.

The difficulty with implementing the concept in our common law jurisdiction is that, for us, the concept of gross negligence exists only in the context of manslaughter, where there is an indifference to an obviously serious risk of death. As a concept, therefore, it is not readily imported into financial services.

It is, however, perhaps unsurprising that PSPs have attempted to argue that customers have been grossly negligent in a wide variety of cases in the context of unauthorised card fraud, and that the FOS and the FCA have responded by scrutinising allegations of gross negligence very carefully – often finding that the PSPs should have applied a 'higher bar' to the concept.

It seems logical that, for a customer to have exhibited a significant degree of carelessness amounting to gross negligence, you first need to establish what the appropriate degree of carefulness might be. In the context of APP fraud scams this is rather challenging as the customer will always have been tricked or scammed, so the most you can do is set out what steps a reasonable customer should take to avoid being scammed. This is exactly what the draft Code does:

- don't ignore PSPs' warnings;

- make sure you respond to a negative confirmation of payee result;

- check that the payee is correct;

- don't recklessly share your passwords and PIN numbers or allow others access to you online banking service;

- be open and honest with your PSP;

- if you are a business or a charity, follow your fraud prevention procedures; and

- don’t be grossly negligent.

We would question whether it is in any way helpful to re-introduce the wooly concept of 'gross negligence' here ('don't be grossly negligent'). It would, perhaps be preferable to keep the above indicators of customer standards of carefulness/carelessness under review and amend them within the Code as expectations change.

When is a customer 'particularly vulnerable' to APP fraud?

A customer should be treated as 'particularly vulnerable' to APP fraud if “it would not be reasonable to expect that customer to have protected themselves, at the time of becoming victim of an APP fraud, against that particular APP fraud, to the extent of the impact they suffered.”

Factors that PSPs should consider when assessing vulnerability, include the personal circumstances of the customer, the impact that the APP fraud has had on them and their individual capacity to engage with financial services and systems.

On the face of it, this broad definition may capture a large number of APP victims – certainly it is open to victims to argue that their circumstances render them vulnerable in a very wide variety of scenarios. This has the potential to reduce the incentive for customers to exercise the requisite level of care and decrease the circumstances in which PSPs can choose not to reimburse their customer. PSPs may also face practical difficulties conducting the case-by-case assessment in ‘real time’ given they are unlikely to know the specific circumstances of a customer, having not identified them previously as being vulnerable.

What are the best practice standards PSPs must meet under the draft Code?

The ‘standards for firms’ cover three core areas: detection, prevention and response, which vary depending on whether the PSP is the ‘sending’ or ‘receiving’ PSP:

- Detection: taking action to identify customers and payments that run a higher risk of being associated with an APP fraud (by analysing transactional data and customer behaviour and training employees).

- Prevention: warning customers about APP fraud; ensuring customers are properly checked and screened to identify high risk accounts; integrating ‘confirmation of payee’ into payment processing; and taking steps to protect vulnerable customers.

- Response: taking action to delay payments in order to investigate suspected APP fraud; communicating with the customer; freezing and repatriating remaining funds and following existing UK Finance ‘Best Practice Standards’.

Do I need to comply with the draft Code now?

No, but retail banks represented on the Steering Group have individually committed to work towards implementing the best practice standards set out in the draft Code straight away and using the proposed customer standards of care when deciding whether to reimburse in APP fraud cases.

The Steering Group is urging other PSPs that provide payment services to follow this example, albeit recognising that certain standards may take time to implement.

Where might the Steering Group come out on the source of funding for reimbursement when both the PSPs and the customer have met the requisite level of care?

The consultation paper sets out several potential approaches, many of which include the creation of a fund from which victims of APP fraud can be reimbursed including:

- getting the whole ecosystem of participants to contribute to a fund (e.g. telecoms companies and data handlers as well as PSPs). This is a nice idea but may be difficult to implement;

- applying a transaction charge on higher risk and high value payments to be directed into a fund. Whilst potentially slowing down high value push payments, this would not discriminate between correct and APP fraud payments, and might have unintended consequences for the UK payments ecosystem;

- if both the PSPs and the customer do not meet the requisite level of care, imposing a fine on the PSPs equivalent to the value of the scam which is transferred into a fund. This assumes that in a scenario where neither the customer nor the PSPs have reached the requisite level of care, the customer would not be reimbursed, which has not yet been decided upon; and

- working with government to set up a scheme which is equivalent to the Criminal Injuries Compensation Scheme. This is a government funded scheme designed to compensate blameless victims of violent crime. Since personal injury does not involve direct financial loss, the value of the payments awarded are set by Parliament and are calculated by reference to a tariff of injuries. The intention is not to fully compensate victims for what they have suffered or lost, it is just society’s way of recognising that they have been a victim. It is not clear whether the Steering Group proposes a similar approach.

The Steering Group has also suggested the use of either voluntary or compulsory insurance policies and pushing for legislative change to unlock dormant funds or redirect funding from FCA or ICO fines.

The Steering Group acknowledges that, until a funding mechanism for a 'no blame' scenario is identified, customers in that scenario might not be reimbursed. This may well be the majority of cases going forwards, so it is vital that this issue is resolved as soon as possible. However, this is clearly a very complex issue. Given that government input may be needed and in light of the diversity of interest groups, it seems to us that the 'early 2019' timeframe for publication of a final Code (at least with this issue resolved) may well be optimistic.

Where might the Steering Group come out on whether customers should be reimbursed when neither the PSPs nor the customer have met their level of care?

Pending resolution of this question, there does not appear to be any consequence for firms if they sign up to the draft Code but then do not adhere to the best practice standards. It has been established that if a PSP meets the best practice standards but the customer does not take the requisite level of care, the PSP will not have to reimburse the customer. It would seem intuitive that the converse should also be true; that if a PSP does not meet the best practice standards and the customer does not take the requisite level of care, the PSP must then reimburse the customer.

It is unclear why the Steering Group has not addressed this issue in its consultation paper and has not asked for input on it. Whilst this scenario is probably the least likely to arise, it is still important to ensure that it has been rigorously worked through.

Osborne Clarke comment

Given the extent of the legal obligations already placed on PSPs in the context of anti-money laundering and fraud prevention, adherence to the best practice standards set out in the draft Code should not require PSPs to make wholesale changes to their existing systems and procedures. In fact, evidence shows that, in general, PSPs already make significant efforts to prevent their customers falling victim to APP scams.

However, there is still plenty of scope for PSPs to enhance their security processes. Those who intend to adopt the Code (either now, or once finalised in early 2019) will need to carefully review their systems, policies and procedures to ensure that they accord with the specific standards of care expected. They will also need to keep their systems under regular review as the Code evolves over time.

Ultimately, the success of the Code will depend upon industry uptake. This requires the outstanding issues identified above to be addressed by the Steering Group in a way which ensures that the Code works on a practical level and provides customers and PSPs with the necessary incentives to comply.

If you are a PSP and considering adopting elements of the draft Code, Osborne Clarke can advise you on the steps you should be taking.