Liability creep | Regulators taking aim at the top

Published on 8th July 2020

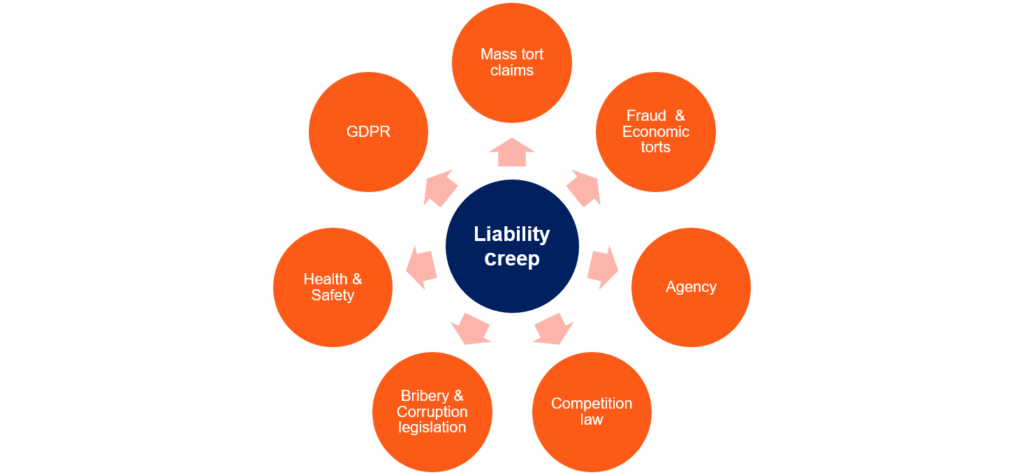

Regulatory regimes such as competition, data protection, and bribery and corruption offer regulators the opportunity to cast the liability net widely across the corporate group. With those regulators taking an increasingly active stance, a joined-up approach to risk management is more important than ever.

Previous articles in this series have explained the growing number of ways in which liabilities relating to the business of one group company can translate into liabilities for other companies in the group, shareholders and/or directors. See our articles on: mass tort claims, economic torts, parent company liability and specific health and safety and 'failure to prevent' offences.

In this article we examine potential liabilities of a regulatory nature, along with potential 'follow on' claims. In particular we focus on competition law infringements, GDPR breaches and bribery & corruption.

Competition law

Competition law pays little regard to the distinct legal status of companies within a group structure, or the distinction between a business and its investor/shareholder. Under competition law, group companies and/or shareholders can be treated as being part of the same "undertaking" where they form a single economic unit. The effect of this is that where one company commits a competition law offence, there is a risk that closely connected companies within the group, and potentially investors, will be held responsible for the infringement. They may be made jointly and severally liable for any fines and be jointly and severally liable for damages in private damages claims brought by those suffering loss as a result of the infringement.

This risk is exacerbated by the fact that fines may well be determined by reference to the turnover of the company fined – this incentivises regulatory authorities to pursue the largest company that can be said to form part of the same undertaking. Furthermore, where there are large scale private damages actions, claimants are also likely to pursue the legal entity with the deepest pockets.

Taken to the extreme, this can include investors such as venture capital funds. An example of this arose in the context of an investment by Goldman Sachs in the Prysmian Group – an Italian business which manufactures power transmission cables. Goldman Sachs was fined EUR 37 million when Prysmian Group, was found to have breached European competition law through its involvement in a cartel relating to power cables. The Commission's decision was appealed but upheld by the General Court in a 2019 decision.

It is now settled in case law that where a parent company exercises "decisive influence" over the conduct of its subsidiary, the two entities constitute a single undertaking and may thus be held jointly and severally liable for the antitrust violation in question and the imposed fine.

Furthermore, there is a rebuttable presumption that a parent company exercises decisive influence over conduct of wholly-owned subsidiary, and over that subsidiary's own wholly-owned subsidiaries. Accordingly, a parent company will be jointly and severally liable for any fine imposed on the subsidiary unless it can show that the subsidiary acts independently.

There is no set proportion of shares that will trigger this presumption: what is required is the exercise of control either directly or indirectly in that company's management. That can be a difficult issue to determine in practice because to some degree shareholders always have some say in the management of a company via shareholder resolutions.

Goldman Sachs argued that it was a mere investor and pointed out that there was no evidence that it played any role in the wrongful conduct or in respect of Prysmian's pricing policy. Furthermore it did not own all the shares. However, the Commission pointed to the fact that although it did not own 100% of the shares in Prysmian, it held 100% of the voting rights and, importantly, it had significant control over the appointment of the board of directors. This control in a general sense was enough to attract liability despite the lack of evidence of any specific involvement in the wrongdoing.

Data breaches

It appears likely that the approach by the European Commission in relation to competition law offences will also be adopted in other areas of European law enforcement, in particular in relation to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The GPDR uses the EU competition law concept of "undertakings" - recital 150 of the GDPR expressly states that "where administrative fines are imposed on an undertaking, an undertaking should be understood to be an undertaking in accordance with Articles 101 and 102 TFEU for these purposes".

As a result, the concept of "undertakings" for the purposes of the GDPR will be closely linked to the concepts of "single economic unit" and the "exercise of decisive influence", as discussed above. European regulators may therefore use this approach to impose liability on parent companies, shareholders or even some investors for GDPR infringements committed by their subsidiaries or investments (where those subsidiaries or investments are subject to the GDPR).

This is important, as fines for non-compliance with the GDPR can be very hefty indeed, up to the higher of EUR 20 million or 4% of an undertaking's global annual turnover. Given the way undertaking is interpreted under EU competition law, the fines that could be imposed are potentially far-reaching. The question of which entities might be liable for fines will depend on how "decisive influence" is exercised within a corporate structure over an infringing subsidiary.

Accordingly, parent and holding companies have a particular interest in ensuring that their subsidiaries are complying with the GDPR in the way they process and transfer data. Likewise, investors should pay close attention to how their target investments collect, store and transfer personal data in order to understand the risks associated with new deals pre-acquisition.

Bribery and corruption

Bribery and corruption is another area where liabilities may spread throughout a group of companies, irrespective of precisely where the wrongdoing occurred.

Under the Bribery Act, for example, a company is guilty of an offence if a person associated with that company bribes another person, intending to obtain or retain business or a business advantage for that company. This offence can be committed in the UK or anywhere in the world and is subject to an unlimited fine.

As a result, a foreign subsidiary of a UK company can cause the parent company to become liable when the subsidiary bribes someone for the benefit of the UK parent. It is an offence of strict liability, so it does not matter that the parent company did not know about or encouraged the subsidiary's activities. However, it will be a defence if the UK company had in place adequate procedures designed to prevent its subsidiary from undertaking such conduct.

Even if the foreign subsidiary was acting entirely on its own account and there is no offence under the Bribery Act, the UK parent might still be liable for the actions of its subsidiary in other ways, for example under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

For example, in 2012, the Serious Fraud Office obtained a civil recovery order against the parent company and shareholder of Mabey & Johnson Ltd, which had bribed public officials in connection with a bridge-building project in Iraq in 2009. The SFO recovered from the parent company the dividends which it had received from its subsidiary arising out of the project, despite that parent having had no knowledge of the unlawful behaviour conducted by its subsidiary, which was acting on its own account. There was no offence under the Bribery Act in this case but the parent company was still handling the proceeds of crime.

What does this means for your business?

A holistic approach to managing risks within corporate groups is essential. This must take into account the duties and risks that arise across a range of legal disciplines, including bribery and corruption, competition law compliance, GDPR, health and safety, data protection and fraud, to name but a few – as well as the myriad ethical and reputational considerations.

What makes this such a difficult exercise is that principles and considerations relevant to different types of risks often pull in different directions. In some contexts, less direct involvement of the parent company in the business of a shareholder is a safer way forward to avoid the risk of liability creep. But in other areas, such as bribery and corruption, parent companies increase the risk of liability if they do not play a sufficiently active role in the supervision of a subsidiary's business.

In some situations (such as mass tort claims), the risk of claims will depend on the specific facts of the parent company's involvement. However, as we have seen above, in the competition law sphere, the mere ability to exert control over a subsidiary's activities can be enough to impose potential liability on the parent company/shareholder in respect of the subsidiary's wrongdoing. This can lead not only to fines but also to liability for individual and collective action damages claims.

All too often, the risks of liability creep are not properly understood or managed because of a siloed approach to risk and compliance. In a world of increasingly active regulators and more group/class action litigation, a joined up approach is essential.