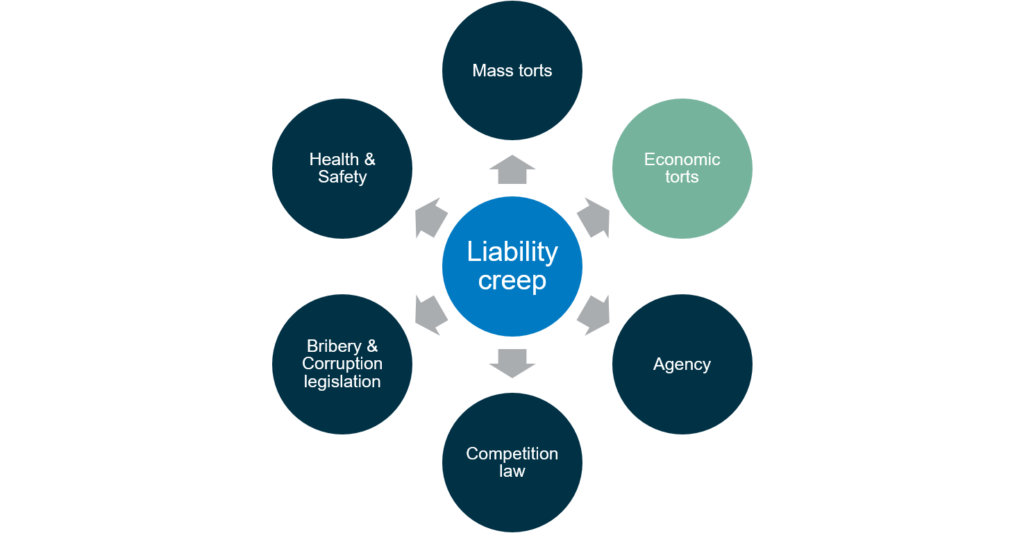

'Liability creep': economic torts widening the net for claimants

Published on 12th February 2020

Unclear lines of authority and decision-making can expose corporates to liability for the actions of other group companies where there are allegations of intentional wrongdoing.

In our first article in this series on 'liability creep', we discussed the recent cases relating to mass tort claims being brought in England against UK parent companies in relation to the actions of their foreign subsidiaries. These mass tort claims were primarily claims for negligence in relation to the safety of employees or environmental claims by local residents affected by the business operations. See our articles in the series on: the actions of regulators, specific health and safety and 'failure to prevent' offences and parent company liability.

In this second article, we focus on ways in which the "economic torts" are being used more and more in commercial disputes to seek to impose liability on shareholders, directors and parent companies, as a means of circumventing the "corporate veil". These are the tort claims of 'procuring a breach of contract', 'conspiracy to cause injury' and 'unlawful interference'. Generally, they involve several different parties and they require some form of intentional wrongdoing.

These sorts of claims often arise where a trading subsidiary is unable to pay its debts or refuses to comply with a contractual obligation and the contractual counterparty or lender wants to seek recourse from a parent company, director or shareholder.

Tort claims allow the aggrieved party to bring an action against those entities/individuals which it asserts have acted in a wrongful (or tortious) manner. This might be different to the entity that it has a contract with. As well as torts relating to negligence, most common law and civil law legal systems allow tort claims to be made against entities that have intentionally caused harm to another where some sort of improper means has been used to cause that harm.

In practice, problems arise for businesses because the nature of competition is that decisions are often made which will cause detriment to someone else. Simply causing harm will not be enough to give rise to a claim. But if there is use of some unlawful means (which might include a breach of contract), combined with a sufficient degree of intention, a claim may arise.

Risks of claims arise in particular where the affairs of the subsidiary are managed or directed by persons other than that company's directors. It may be shareholders who call the shots, or it may be that decisions are made by a divisional management structure which bears little relation to the legal structure of the group.

This means that the more a parent company, executive or shareholder is involved in the running of another group company, the greater chance of an exposure to liability for an economic tort in circumstances where that other company cannot satisfy its obligations to third parties. A particular area which may raise risks is where a group's finances or assets are ordered in a way that might impact on third parties. We set out examples of potential problems below.

Key elements of the economic tortsThe key elements of the three main economic torts are as follows:

|

What might trigger liability

Consider the situation where a corporate group has an international business division selling goods in Europe and the US. The head of that business division is an individual in the US, employed by the US parent company of the group. The UK subsidiary makes a commercial decision to act in breach of one of its contracts. If the head of the business division was behind that decision, that person or the US parent company might become the subject of a tortious claim for procuring a breach of contract.

Where a parent company refuses to fund a subsidiary (and is under no legal obligation to do so), so that it can't perform its obligation under a contract, that will not amount to the tort of procuring or inducing a breach of contract. However, dissipating the subsidiary's funds (where, for example, the parent company has sufficient control over those funds), making it impossible for the subsidiary to meet its contractual commitments, might well trigger liability under one or more of the economic torts.

Where a group company (A) refuses to supply raw materials to another group company (B) in order to harm a third party with whom B has entered into a supply contract, this may trigger liability for causing loss by unlawful means. Of course, the subsidiary or group company may not be an unwilling party to the parent company's actions. Where the group companies act in concert, this could amount to conspiracy to injure by lawful or unlawful means.

Containing the risks

The following practical steps can help to minimise the risk of attracting liability:

- Where decisions are taken by shareholders or the parent company, which might impact on the ability of a company/subsidiary to fulfil its contractual commitments, record the rationale behind those decisions. As the economic torts usually require an intention to harm, contemporary evidence demonstrating the "benign" reason for a decision could be a decisive factor in any future litigation.

- Ensure the appropriate corporate decision making structure is followed and document that decision making. So far as possible, individuals in one company should avoid having direct control over the decisions of another group company.

- Clearly delineate the roles of individuals within a group of companies and consider the capacities in which they are acting.

- Where contracts are entered into with third parties, make clear on which company's behalf the person signing the contract is acting.

- Shareholders exercising control should do so by way of shareholder resolutions rather than by acting as de facto directors.

It is not possible to exclude all risk, but taking care over these practical points is a good start.