Decarbonising supply chain disputes through effective contract management

Published on 7th September 2021

With businesses increasingly focused on environmental, social and corporate governance, how can the resolution of disputes via arbitration be made greener for all involved while still ensuring maximum efficiency and cost-effectiveness?

Environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) criteria have become a central component of effective corporate governance. The risks posed by climate change are now at the forefront of the boardroom agenda. Coordinating an ESG policy that fit into a company’s corporate strategy can be a daunting task, in particular in globally operating businesses with complex international supply chains. The green drive is also starting to affect the conduct and management of disputes.

Arbitration, the dispute resolution mechanism of choice for companies of all sizes operating internationally, tends to have a high carbon footprint. This is normally due to the large amount of travelling involved and the volume of paper generated during a typical dispute — in November 2019, an environmental impact assessment conducted by the Campaign for Greener Arbitrations found that more than 20,000 trees would need to be planted to offset the carbon emissions from a single medium-sized commercial arbitration. Another principal cause of carbon-rich disputes is the lack of a bespoke dispute resolution process that takes into account the legal relationships between different links in the supply chain and the types and causes of disputes that may arise during a project or transaction.

Case study: typical supply chain arbitration

It is highly unlikely that an entire supply chain will be governed by a single contract. International supply chains are particularly susceptible to inefficient and carbon rich disputes due to the matrix of contracts with often diverging dispute resolution clauses.

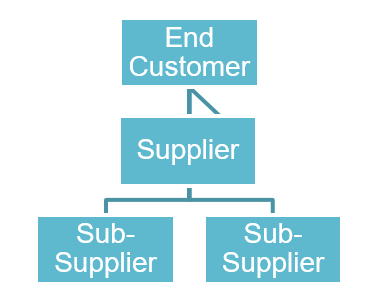

Taking the example of a simple supply chain involving an engine for a wind turbine — the end customer contracts with a supplier for an engine. The supplier sources individual components, for example bearings and gearboxes, from sub-suppliers, before assembling them and delivering the engine to the end customer. The end customer will typically only have a contract with the supplier. The supplier will have individual contracts with its own suppliers. In practice, these contracts usually contain dispute resolution clauses providing for different laws and for disputes to be heard by disparate tribunals.

Taking the example of a simple supply chain involving an engine for a wind turbine — the end customer contracts with a supplier for an engine. The supplier sources individual components, for example bearings and gearboxes, from sub-suppliers, before assembling them and delivering the engine to the end customer. The end customer will typically only have a contract with the supplier. The supplier will have individual contracts with its own suppliers. In practice, these contracts usually contain dispute resolution clauses providing for different laws and for disputes to be heard by disparate tribunals.

Imagine that the bearings corrode and crack and the gearboxes overheat. The end customer and supplier cannot agree on a settlement. The end customer commences arbitration against the supplier. Even though the supplier is not at fault for the root cause of the defects, it is still contractually liable to the end customer. The supplier will be ordered to pay damages to the end customer due to failures of the components. The supplier will then have to claim its losses from its sub-suppliers in separate proceedings.

This will inevitably result in the same issues being rearbitrated, even though the dispute between the supplier and its sub-suppliers arise out of exactly the same facts. The complexity will increase if these proceedings run in parallel which increases the risk of inconsistent decisions. A new tribunal will be presented with a fresh set of pleadings and exhibits even though they may be substantively the same as those in the prior proceedings. Witnesses will have to be re-examined. Experts will have to conduct more investigations with findings that overlap with previous findings. Inconsistencies may lead to follow-on litigation or arbitration. There will be additional hearings which will require more travel and additional papers. Not only will this generate considerable excess costs, it will create a significantly larger environmental impact than having all issues decided by one tribunal in one set of proceedings.

Focus on contract management

There are things that businesses can do at the contract stage that may avoid the above scenario. An efficient and environmentally conscious dispute resolution policy may include the following hallmarks:

- Uniformity in the supply chain: Customers and suppliers may be able to agree on a framework dispute resolution agreement, which, where possible, means that the dispute resolution procedure is consistent across the supply chain.

- Consolidate claims and join suppliers: Many institutional arbitration rules, such as the ICC Rules and LCIA Rules, provide for some form of consolidation and joinder — businesses should ensure that their arbitration agreements are drafted in such a way that these will work.

- Expedited procedure: Many institutional arbitration rules also provide for some kind of expedited procedure, offering a compressed timetable. Although in principle intended for low value disputes, they can in appropriate cases be extended to higher value disputes and could help to reduce the carbon footprint of proceedings in combination with the other points in this list.

- Agree to a remote hearing in advance…: Parties may be best served by agreeing in advance to a remote hearing and the protocol for the management of any remote hearings. Experience has shown that remote hearings can be successful and there are clear environmental advantages in not having to travel. Once a dispute has arisen, reaching agreement with a counterparty as to how a dispute should be conducted may be more difficult. See our recent video on remote hearings.

- …Or dispense with a hearing entirely: Remote hearings still have a carbon footprint due to the energy needed to operate computers and servers. It might be worth having cases decided on (electronic) documents only rather than having a hearing at all, especially in smaller, less complex or lower value cases. This can be provided for in an arbitration clause, either expressly or by reference to institutional rules that offer a documents-only procedure.

- Go paperless: Forego hard copies in favour of submitting documents electronically by email or file transfer. If a hearing is necessary, then electronic hearing bundles will save time, costs and be much greener at the same time as being more efficient for all involved.

- Utilise existing contractual and procedural frameworks: Various initiatives have been started by legal practitioners to encourage green contracting and green arbitrations. The Chancery Lane Project is a collaborative effort from lawyers from around the world to develop new contracts and model laws to help fight climate change. Sample clauses include the avoidance of excessive paperwork in dispute resolution and low carbon arbitration hearings. There is even a clause proposing that the governing law is interpreted in a manner consistent with the objectives of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement. The Campaign for Green Arbitrations is an effort to facilitate greener arbitration proceedings. A set of Green Protocols aims to promote better environmental behaviour. The protocols are intended to serve as practical guidance for users for implementing the Guiding Principles of Green Arbitrations for all stakeholders involved in the practice of arbitration, from parties and their lawyers to arbitrators, hearing venues and institutions. There is also a Model Green Procedural Order, which suggests directions such as electronic communications and electronic service of documents, remote meeting of witnesses and experts and remote hearings, including for substantive hearings as well as procedural ones.

- Green alternative dispute resolution (ADR): Inspired by the Green Pledge which led to the creation of the Campaign for Greener Arbitrations, the mediation community has created the World Mediators Alliance on Climate Change, which has developed its own Mediator's Pledge. Much like the arbitration pledge, the Mediator's Pledge encourages mediators to consider and minimise their impact on the environment, including encouraging environmentally friendly travel, use of video technology and electronic correspondence. In seeking to avoid or settle disputes, parties can also consider green ADR processes.

Osborne Clarke comment

An environmentally friendly dispute resolution process also tends to make it more efficient and more cost-effective. Our experience of supply chain arbitrations such as the one in the case study above has shown what a large environmental impact a typical dispute can have. Remote working and remote arbitration hearings, in particular during the Covid-19 pandemic, have been just as effective as traditional in-person hearings. The extent to which ESG frameworks and green initiatives have been developed and acted upon suggests that companies will be able to manage their differences and disputes in a sustainable manner in future. Companies may even consider including requirements for greener dispute resolution practices in their contracts from the outset, where possible.

Parties to arbitration proceedings must, however, remain conscious of the need to reconcile their sustainability objectives with the wider objective of an efficient and effective arbitration process and the delivery of a robust and enforceable award.