Are parents to blame? Liability in mass tort claims

Published on 12th February 2020

This article is part of a series focusing on the different ways in which liability for the actions of one group company may end up being borne by other group companies, its managers or investors.

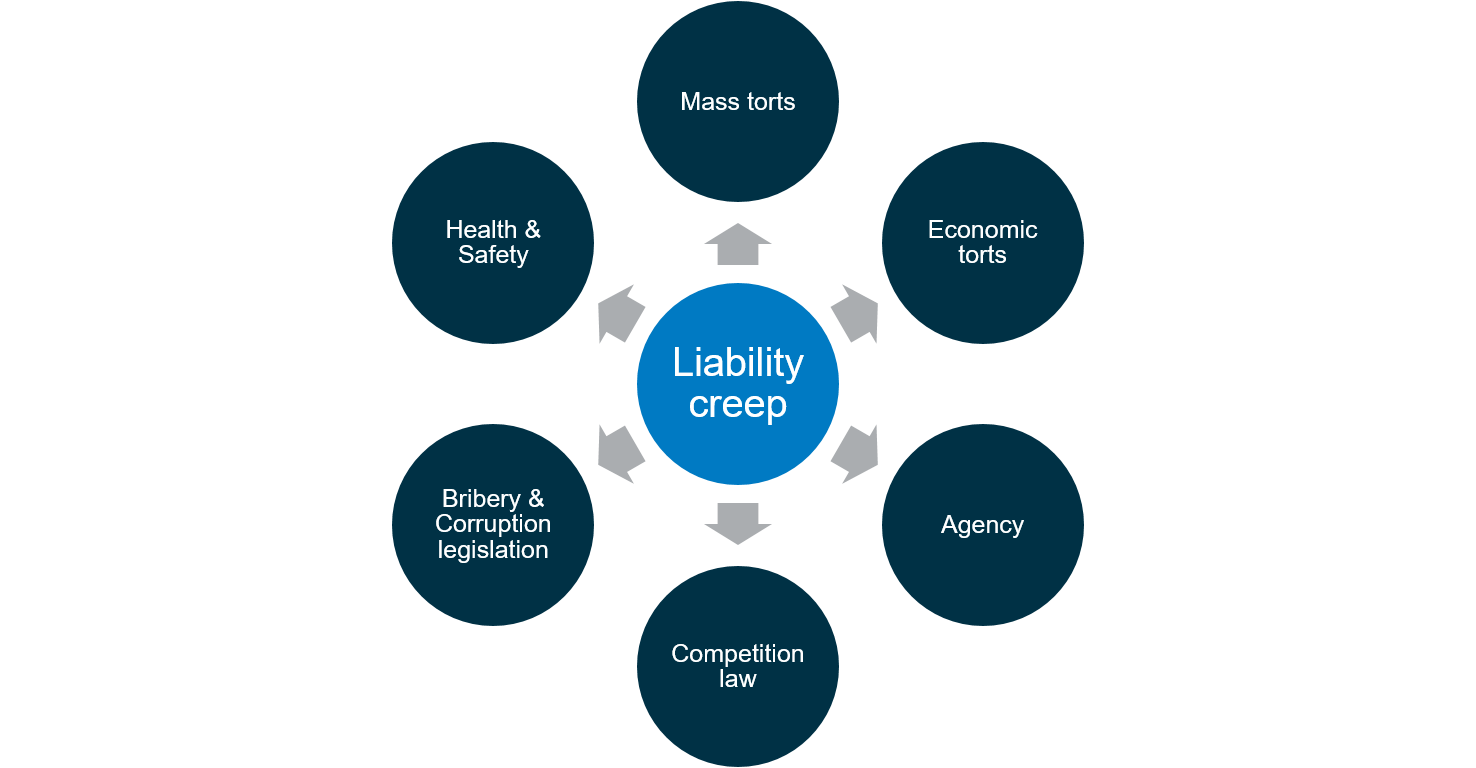

The issue of 'liability creep' is an important one for companies and their directors and shareholders across all sectors both from a regulatory and risk management perspective. Private equity investors, in particular, need to be wary of inadvertently assuming liability for the actions of target companies.

In this article we consider the risks of parent companies being liable for mass tort claims relating to the actions of foreign subsidiaries. There has been a trend in recent years in overseas claimants bringing proceedings in the English courts against UK parent companies for the actions of its foreign subsidiaries. Overseas claimants often wish to bring claims in England, rather than in their jurisdiction of domicile, where for a variety of reasons they may consider that there is no real prospect of recovering significant damages.

An important jurisdictional case that reached the Supreme Court last year emphasises that the legal separation of companies in itself is not enough to avoid parent company liability – or at least the realistic prospect of it, which can be enough to enable the claimants to pursue their claim in the English courts. We consider the impact of this decision and what it means for your business/investments.

Vedanta: no special principles for establishing parent company liability

The Supreme Court's landmark ruling in Vedanta Resources PLC v Lungowe and others highlights the sort of issues that UK parent companies can face.

The Zambian claimants, who live near a copper mine which is owned and operated by Konkola Copper Mines (KCM), brought claims in the English courts against both KCM and Vedanta (its English domiciled parent company). The claims concerned loss and damage suffered as a result of pollution which was allegedly caused by emissions from the mine. Vedenta contended that the English court did not have jurisdiction to hear the dispute.

The Supreme Court found that the English courts did have jurisdiction to hear the claims brought against Vedanta and KCM because:

- there was a real issue to be tried against Vedanta, as it was reasonably arguable that Vedanta owed a duty of care to the claimants for the conduct of KCM;

- KCM was a necessary and proper party to the claim; and

- although Zambia would be the most appropriate forum for the claim to be heard, there was a real risk that substantial justice could not be done in Zambia, and as such the English courts should take jurisdiction over the claim.

The Supreme Court held that there are no special principles for establishing parent company liability for the conduct of a subsidiary, and that the usual test of foreseeability, proximity and reasonableness applies (as set out in Caparo v Dickman). Lord Briggs (who gave the Supreme Court's judgment) noted that there are limitless ways in which management and control may be implemented in multinational group companies, varying from the parent being only a "passive investor" in a separate business carried out by its subsidiaries, to a vertically integrated group which is managed as a single company.

The key question was whether Vedanta had sufficiently intervened in the management of KCM's mine to have incurred a duty of care to the claimants. The parent/subsidiary relationship merely demonstrated that Vedanta had the opportunity to incur a duty of care towards the claimants, but whether it had or not would depend on the extent to which it had "availed itself of the opportunity to take over, intervene in, control, supervise or advise the management of the relevant operations (including land use) of the subsidiary".

In essence, a parent company is at greater risk of incurring a duty of care where it is closely involved with the management of its subsidiary's business, particularly where it imposes group-wide policies on its subsidiaries. Lord Briggs noted that a parent company may expose itself to liability where it imposes group-wide policies or guidelines containing systemic errors that cause harm to third parties when implemented by its subsidiary.

Likewise, even where the policies themselves do not give rise to a duty of care to third parties, a parent company may still incur liability if it takes active steps ensure that the group-wide policies are implemented by its subsidiaries (for example, via training, supervision and enforcement), or where the parent publicly purports to supervise or control its subsidiaries when in reality it does not. However, the Supreme Court's jurisdiction decision was not a final decision that there was a duty of care, and the case will now proceed to trial to determine whether Vedanta did in fact owe the claimants a duty of care.

What does this means for your business?

The question of whether a parent company, or an investor, might be held responsible for the actions of a subsidiary is fact sensitive and the potential for attracting liability will depend on how the business is actually structured and operated. The legal separation of group companies is not enough.

Multinational companies, and their investors, should be mindful that group-wide policies may give rise to a parent company duty of care, where the parent or an investor takes active steps to implement policies in its overseas subsidiaries/portfolio companies. Careful consideration of the language used in published materials (such annual reports) is also required, as it may give rise to a duty of care if it could be interpreted as asserting responsibility for the supervision or control over the operations of subsidiaries (even if such supervision or control is not exercised).

These considerations are particularly important for UK-headquartered companies and their investors where the group has subsidiaries in developing countries. In Vedanta, the Supreme Court held that whilst England was not the most appropriate forum in which to bring proceedings against KCM, the English courts should nevertheless accept jurisdiction, as there was a real risk that substantial justice would not be obtained in Zambia.

These risks have to be carefully balanced against the corporate governance interest to implement policies and practices in overseas subsidiaries in order to prevent acts that may give rise to a claim in the first place. This is difficult to manage given that more and more 'compliance' regulation requires UK-domiciled parent companies to put in place adequate systems to avoid wrongdoing in their overseas subsidiaries, as well as branch offices. Businesses are also subject to an increasing focus on ethical and responsible business practices – from business partners, shareholders and employees, as well as the public. Group-wide policies and reporting can play an important part in ensuring that core business values are being upheld across their global footprint.

Investors will be keen to ensure that any of these legal, regulatory and compliance risks, which are present in their portfolio companies, do not rebound up the investment chain – for example by putting in place the appropriate policies and procedures. However, there is an inherent tension: the more investors are seen to be controlling their portfolio companies, the greater the risk that they will incur liability.

A holistic approach to managing risks within corporate groups is therefore essential. This must take into account the duties and risks that arise across a range of legal disciplines including bribery and corruption, competition law compliance, health and safety, data protection and fraud, to name but a few – as well as the myriad ethical and reputational considerations. However, simply doing more is not always the right answer.